A book review of “Describing Inner Experience? Proponent Meets Skeptic” by Russell T. Hurlburt and Eric Schwitzgebel (2007)

A couple of years ago I realised I didn’t have a visual imagination.

This was ultimately quite inspiring – it’s led me to ask maybe a hundred people about their own inner lives. The answers so varied, I’m left in wonder at this hidden world that we barely talk about.

My favourite source about this is “The pheneomena of inner experience” (a paper by Heavy, Hurlburt 2008). It uses a method (Descriptive Experience Sampling, or DES) to randomly beep a bunch of volunteers in their every day lives, and get them to then capture their current mental phenomena.

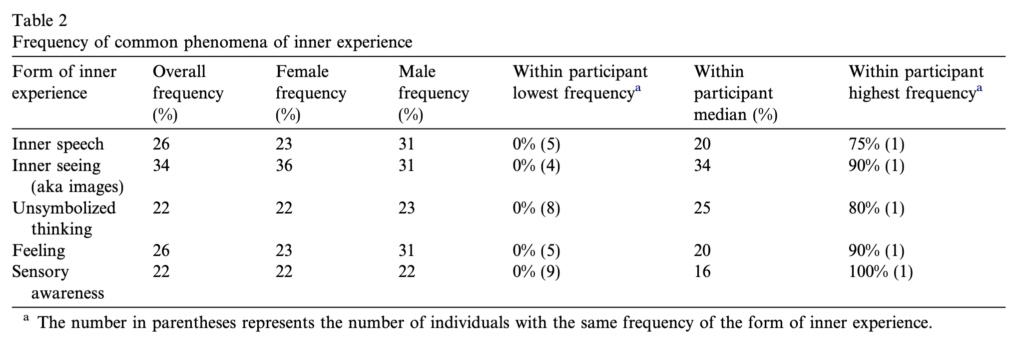

The kicker is this beautiful table 2. It lists the top 5 most common forms of inner experience. For each one there were participants who never experience it and other participants who experience it more than 75% of the time.

Just pause a moment to absorb that.

Take something that you feel is fundamental to life, to your experience of being conscious. For example, that you have an inner voice, or that you’re aware of your senses, or that you imagine visual imagery. For that thing, which you might be doing >75% of the time!, there are substantial numbers of otherwise ordinary people who never do it at all.

We are not remotely in the same world.

And so (via mention in a New Yorker article recommended by Anna), to “Describing Inner Experience? Proponent Meets Skeptic“, a 2007 book also by DES proponent Hurlburt, with sceptic Schwitzgebel.

It’s framing account is a dispute between the psychologist and philosopher authors, but honestly that is a bit of a side show. It feels like it mainly consists of Schwitzgebel assuming other people have inner experiences like him, which they don’t. Hurlburt is very patient, and the discussions reveal a lot.

No, the important part is the individual experiences of their subject, Melanie. She’s a philosophy and psychology graduate, and you get the sense that in many ways she knows more than the older men writing the book.

The book consists of detailed dialogues in which Melanie recounts her experiences at the moment of a random beep, and Hurlburt quizes her openly and intelligently to unpack and improve the quality of that description.

Melanie’s world is not like mine. It’s not so different, but it is not the same. Just as in user testing, the first sample is worth a fortune compared to no samples at all. These specific, concrete details of how someone else experiences being alive are inspiring and enlivening. They made reading the book worthwhile.

I’ll give two striking examples.

On the first day, Melanie sees emotion as a colour. She’s laughing at something to do with the documentation for a piece of furniture she’s assembling. Along with a verbal thought that it is funny, she gets a “kind of rosy yellow glow” in her head, all over like a “wash of color”.

Melanie says “It was a feeling that was very familiar to me, or I guess, the sight, you could say, of this colour that is really familiar to me and is one that I commonly associate with laughing at a joke or something that involves humour”.

I struggle to associate emotion, as is fashionable, with part of my body. It feels conceptual to me, simply raw emotion. To get a colour for an emotion is even more striking to me.

Schwitzgebel doubts she really sees the colour, mainly because he never does and because the literature never mentions it. Even when, in the end section, Schwitzgebel digs into that literature I’m unconvinced. Unlike DES, previous methods never attempt to get decent, normal accounts of inner experience.

They seem to mainly consist of philosophers who assume everyone has the same experience as them, and introspect in their arm-chairs using ineffective techniques… Or of more low level set experiments trying to catch subtle details like the experience of the third soft resonance tone when playing two notes.

For some other similar accounts of synaesthetic emotion, this site assembles lots of reports from Reddit.

Much later, Melanie has an echo of her inner voice. She’s tidying up some dead flower petals in the sink, and thinks “They lasted for a nice long time” in her inner speech voice. That’s called “articulatory” – it is the inner voice that feels like you’re almost speaking.

Then, overlapping with that and repeating on top of itself several times like an echo, she inner hears her own voice saying “nice long time” “nice long time” “nice long time”…

Schwitzgebel doubts this one too. At first that it happened at all, and then focussing on the timing. Melanie reports the echo happening in a very small amount of real time. She felt all of the words in full, yet little actual time passed.

Doubting this seems bizarre and excessive to me. We know for sure from examining the strategic planning our minds must be doing, that we can run reasonably high fidelity simulations of almost anything very rapidly. We don’t experience them, and we don’t know what form they’re in, but a compressed detailed modelling of some kind must be happening rapidly.

In dreams time is often odd, they can feel like a long time when it’s only ten minutes since you pressed the sleep alarm. My instinct is the opposite of Schwitzgebel – of course time isn’t always real within our conscious experience! So I find it difficult to take him seriously.

The book ends with summary notes from each author reflecting and responding. Neither change their view. Hurlburt is happy with his life’s work developing DES, and Schwitzgebel is happy with his life’s work beind cynical about what we know about our inner experiences.

They bring in a bunch of interesting research history. At the end of the C19 there was a critical argument between Titchener, who believed all thought consisted primarily of images, and Würzburg who believed in intangible mental activities. They both did research which apparently crashed and collapsed, and the quick summary is that everyone then ran to behaviouralism and stopped thinking about inner experience.

I’m being an armchair introspector, which the book dislikes, but I really do think I don’t have very much visual imagery. It’s barely tangible, and usually just spatial without colour or texture. This makes it hard for me to take Titchener, or any of his research, or anyone who references him, very seriously. Especially now there are MRI scans to show there really are radical differences in visual imagination.

Another fun reference was to Flavell, who in the 1990s researched the inner experiences of 5-year olds. It came out that they aren’t aware of their thoughts, even quite socially visible and important ones that their behaviour showed they were having. Flavell concluded that they must have been thinking and therefore their reports and research is wrong. When actually, perhaps 5-year olds have a less developed form of consciousness, and “just do” more without specific conceptual, visual or verbal awareness. This definitely feels like it needs more investigation, and we’d learn a lot.

Hurlburt ends by describing the difference between research that aims to explore and discover, vs research that tries to prove a theory. He says that introspection philosophy and psychology keep trying to jump ahead and test theories. I agree with him that it is too soon to do that, we don’t understand how the mind works at all.

We seem to be missing basic information about how different our inner worlds are from each other. We should use tools like DES, and develop more like it, and get many more people to introspect. We can grow our language and capabilities as a society.

Then perhaps we’ll have the tools and information to make theories, and understand more about that mystical experience of being a conscious being.

Dear Francis, a very reasonable article.

I heartily agree that many academics are a bit assertive over what other people must or must not be doing while they think, something I noticed talking to my college philosophy tutors.

You & I corresponded briefly some years ago about some web-coding work you’d done. I seem to recall you had worked on the They Work For You site collating details about MPs. There’s also a dim memory somewhere in my mind that you were born in Shanghai??

What are you doing to keep the wolf from the door these days?

Mark

Thanks Mark for the comment! Will reply to you by email!